Who Should Be Concerned About Erythritol Intake?

Author: Dr. Stephen Chaney

Everyone is searching for the perfect sweetener. And if you were in the marketing department of Big Food Inc, the perfect sweetener would be defined as:

Everyone is searching for the perfect sweetener. And if you were in the marketing department of Big Food Inc, the perfect sweetener would be defined as:

- Natural, meaning that it is found in fruits, vegetables, or other plant foods.

- Low in calories. Of course, a perfect sweetener would have zero calories because it is not metabolized in our bodies.

- Low glycemic, meaning that it would have a minimal effect on blood sugar levels. Once again, a perfect sweetener would have zero effect on blood sugar levels.

- Safe, meaning that it has no adverse effects on our health.

Sugar alcohols appear to meet all these criteria, so they have become the sweetener of choice for lots of highly processed foods. This is especially true for the sugar alcohol, erythritol, since it is currently the least expensive of the sugar alcohols.

So, a recent study (M Witowski et al, Nature Medicine, 2023) suggesting that erythritol might increase the risk of heart disease was quite surprising.

This is the first study to suggest a link between erythritol and heart disease, and it was a flawed study (I will discuss the flaws below).

Reputable scientists don’t put much credence in a weak first study like this one. We generally consider the conclusions of a first study like this one to be an unproven hypothesis at this point.

But we are cautious. There will be many follow-up, better designed studies, to test this hypothesis. Once these studies have been published, the scientific community will look at all the evidence and either issue a warning or conclude that there is no reason for concern.

But that doesn’t stop the Dr. Strangeloves of the world from warning you of the “dangers” of erythritol and telling you to avoid it at all costs.

For that reason, I felt it was appropriate to address this issue. I will:

- Describe the study and its flaws.

- Put the study into the broader perspective of what we know about sweeteners.

- Identify the two population groups who should be most concerned about erythritol.

How Was The Study Done And What Did It Show?

This study can be divided into three parts.

#1: An Association Between Erythritol Blood Levels And Heart Disease.

#1: An Association Between Erythritol Blood Levels And Heart Disease.

There were three separate experiments included in this section of the study. In each experiment patients were recruited after visiting cardiac clinics for diagnostic procedures. The average age of these patients was 67 and 45% of them already had experienced a non-fatal heart attack prior to the study. In other words, these were all older patients with pre-existing heart disease who were at high risk of heart attack or stroke in the near future.

The first study was a metabolomic study. In simple terms this means that high-tech equipment and computing were used to measure hundreds of metabolites in the blood of the patients and, in this case, correlate each of them with the occurrence of heart attacks and strokes over the next three years.

- This study identified 16 sugar alcohols and related metabolites in the blood of these patients that were associated with an increased risk of heart attack and stroke. (I will discuss the significance of this observation in more detail later.)

Because erythritol was among the top 6 compounds in terms of association with increased heart attack and stroke risk, and erythritol is the most commonly used sugar alcohol in processed foods, the next two studies focused on the association between blood levels of erythritol and heart attack/stroke risk. Their results were predictable.

- High blood levels of erythritol were associated with an increased risk of heart attack and stroke over the next three years.

Flaws In This Portion Of The Study:

- As the authors of the study pointed out, these studies were done with older patients with pre-existing heart disease who were at high risk of heart attack or stroke. They acknowledged that it is not known whether these associations exist with younger, healthier patients.

- As the authors also pointed out, these are associations. They do not prove cause and effect. In particular, the studies did not measure the diet, exercise habits, and other lifestyle factors of these patients that may have contributed to their increased risk of heart attack and stroke.

- When you look closely at the data, it is clear that the association is only seen at the highest blood levels of erythritol. Specifically, the blood levels of erythritol in these patients were divided into quartiles. The risk of heart attack and stroke in the first three quartiles (low to moderate blood levels of erythritol) were identical to the control. However, the fourth quartile (highest blood levels of erythritol) was associated with a dramatically increased risk of heart attack and stroke. That raises three important questions:

-

- “How much erythritol were patients in the fourth quartile consuming?”

-

-

- The authors did not look at dietary intake of erythritol but did note a previous study estimated that Americans consume up to 30 grams of erythritol a day.

-

-

- 30 grams of erythritol a day is a huge amount of erythritol. Where does that erythritol come from?

-

-

- Much of it comes from erythritol-containing highly processed foods like zero calorie sugar substitutes (either erythritol alone or erythritol mixed with artificial sweeteners to improve the taste); reduced- and low calorie carbonated and non-carbonated beverages; hard candy and cough drops, cookies, cakes, pastries, and bars; puddings and pie fillings; soft candies; syrups and toppings; ready to eat cereals; fruit novelty snacks; and frozen desserts.

-

-

-

- But it is also found in foods you might not suspect, such as plant-based “milk” substitutes; chocolate and flavored milks; barbecue and tomato sauce, fruit-based smoothies, the syrup used in canned fruits, yoghurt; low calorie salad dressings; and salty snacks.

-

-

-

- In other words, the only way anyone can consume 30 grams of erythritol in a day is to consume large quantities of erythritol-containing highly processed foods (I will discuss the significance of this observation later).

-

-

- “What else was different about patients in the fourth quartile?”

-

-

- When you look carefully at the data, the patients in the fourth quartile were significantly older, with a higher incidence of diabetes, pre-existing coronary artery disease, previous non-fatal heart attacks, congestive heart failure, and greater triglycerides – all of which significantly increase their risk of heart attack and stroke.

-

#2: Mechanistic Studies:

Next the authors did in vitro and animal studies looking at the effect of high levels of erythritol on blood clotting.

- These studies showed that high levels of erythritol promoted blood clotting both in vitro and in mice. The authors concluded that these studies provided a plausible mechanism for a link between high erythritol blood levels and increased risk of heart attack and stroke.

Flaws In This Portion Of The Study:

- Other critics have pointed out that the assays used were not accurate models of blood clotting in humans. This particular critique is beyond my expertise, so I won’t comment further. However:

-

- As someone who was involved in cancer drug development for over 30 years, I know that in vitro and animal models are poor indicators of how things work in humans.

-

- And as a biochemist, I have two concerns:

-

-

- The authors provided no mechanistic rationale for why erythritol would enhance blood clotting.

-

-

-

- The authors made no effort to show that the effect of erythritol was unique. Would high levels of other sugar alcohols or other naturally occurring sugars have the same effect on blood clotting in their assays? We don’t know.

-

#3: Blood Levels Of Erythritol After Oral Intake.

Finally, the authors gave subjects 30 grams of erythritol and measured blood levels over the next several days.

- This experiment showed that very high blood levels of erythritol were attained and maintained for at least two days before gradually decreasing to baseline. The authors concluded this experiment showed that it was feasible to attain and maintain high blood levels of erythritol for several days following a single ingestion of 30 grams of erythritol.

Flaws In This Portion Of The Study:

- I have already pointed out that 30 grams per day is a huge amount of erythritol. However, erythritol in the diet will come from a variety of foods, some of which will contain components (fiber etc.) that slow the absorption of erythritol.

- In contrast, the subjects in this experiment were given 300 ml of liquid containing 30 grams of erythritol and told to drink it in two minutes!

- In other words, these subjects were consuming 30 grams of erythritol in 2 minutes rather than 24 hours, and they were consuming it in the most easily absorbable form. For a study like this, that makes the effective dose orders of magnitude greater than the amount of erythritol that anyone consumes from their diet over a 24-hour period. The study design was completely unrealistic.

Is Erythritol Bad For Your Heart?

As described above, this is the first study to suggest an association between erythritol and heart disease, and it was a highly flawed study.

As described above, this is the first study to suggest an association between erythritol and heart disease, and it was a highly flawed study.

It is also important to know that erythritol is not an artificial sweetener. It is found naturally in foods like grapes, peaches, pears, watermelons, and mushrooms. It is also found in some fermented foods like cheese, soy sauce, beer, sake, and wine.

It is also a byproduct of normal human metabolism, so we always have some of it circulating in our bloodstream. Our body knows how to handle low to moderate intakes of erythritol.

However, to help you really understand what this study means, I need to put it into the context of other studies. I will do this in story form (You will find more details about these studies in my book “Slaying The Food Myths”).

First, let’s look at highly processed food consumption:

- Multiple recent studies have shown that high consumption of highly processed food is associated with increased risk of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and premature death. We don’t know what it is about highly processed food consumption that is responsible for the increased risk, but it is unlikely to be just one thing.

- As I pointed out above, the only way to achieve the high blood levels of erythritol associated with increased heart disease risk is to consume large quantities of erythritol-containing highly processed foods.

Next, let’s follow the history of sweeteners in highly processed foods.

- When I was a young man, sucrose (table sugar) was added to most highly processed foods. Sucrose is found

naturally in many fruits and vegetables. Small to moderate intake of sucrose in unprocessed and minimally processed foods posed no problem. However, large intakes of sugar in highly processed foods were found to increase the risk of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and premature death.

naturally in many fruits and vegetables. Small to moderate intake of sucrose in unprocessed and minimally processed foods posed no problem. However, large intakes of sugar in highly processed foods were found to increase the risk of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and premature death.

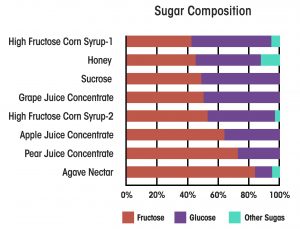

- At that point, sucrose became a “sugar villain”, and Big Food, Inc substituted fructose and high fructose corn syrup (a mixture of fructose and glucose) for sugar in their highly processed foods. As with sucrose, fructose is found naturally in many foods, and small to moderate intakes of fructose and high fructose corn syrup posed no health risks. However, large intakes of fructose and high fructose corn syrup in highly processed foods were found to increase the risk of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and premature death.

- Fructose and high fructose corn syrup then became the sugar villains. And because high fructose corn syrup is chemically and biologically indistinguishable from natural sugars like honey, date sugar, coconut sugar, it is likely that high intakes of these sugars in highly processed foods would cause the same problem.

- So Big Food, Inc started relying on artificial sweeteners in their highly processed foods. But guess what?

Recent studies have suggested that artificial sweeteners in highly processed foods are associated with obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

Recent studies have suggested that artificial sweeteners in highly processed foods are associated with obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

- That has caused Big Food, Inc to rely more on sugar alcohols in their highly processed foods, particularly erythritol because it is the least expensive of the sugar alcohols. Now the current study comes along and suggests that high intake of erythritol in highly processed foods may increase the risk of heart disease.

- If this hypothesis is confirmed by better designed studies, it is not clear what Big Food, Inc will do next. The metabolomic study described above showed that high blood levels of several other sugar alcohols are associated with an increased risk of heart disease.

Hopefully, you are starting to see a pattern here. It’s time to ask the question, “Is it the sweetener, or is it the food?”

Clearly, it doesn’t matter what sweetener we are talking about. Large intake of any natural sweetener in the context of a diet rich in highly processed foods appears to have an adverse effect on our health. And we don’t know whether these adverse health effects are caused by the sweetener or some other component of the highly processed foods.

If you want to improve your health, the best solution is to decrease your intake of highly processed foods. That will automatically reduce your intake of sweeteners and other unhealthy components of highly processed foods and increase your intake of healthy components from the whole foods you will be eating instead.

Who Should Be Concerned About Erythritol Intake?

The authors of this study identified two groups who should be most concerned about erythritol consumption – diabetics and adherents of the keto diet.

- Diabetics are at high risk because they are told to consume non-caloric sweeteners instead of sugars, and they are not told to avoid highly processed foods. Consequently, they consume much higher amounts of non-caloric sweeteners than the average American.

- I must admit that I didn’t foresee keto adherents as a high-risk group. However, it appears that keto enthusiasts love their sweets as much as the rest of us, and the sweetener of choice for keto-friendly sweets is erythritol. The authors said that a single serving of keto ice cream contains 30 grams of erythritol. I can hardly imagine how much erythritol they must be getting in their diet.

And, once again, the best advice for both groups is to simply decrease the amount of highly processed food in their diet.

The Bottom Line

Erythritol is not an artificial sweetener. It is found naturally in foods like grapes, peaches, pears, watermelons, and mushrooms. It is also found in some fermented foods like cheese, soy sauce, beer, sake, and wine.

It is also a byproduct of normal human metabolism, so we always have some of it circulating in our bloodstream. Our body knows how to handle erythritol.

That is why it was a surprise when a recent study claimed that high intake of erythritol is associated with an increased risk of heart attack and stroke. The Dr. Strangeloves of the world are already starting to tell you that erythritol is deadly and you should avoid it at all costs. But reputable scientists are saying, “Not so fast”.

This is the first study to suggest an association between erythritol and heart disease, and it was a highly flawed study.

In fact, the study showed that low to moderate intakes of erythritol had no effect on heart disease risk. It was only the highest intake of erythritol that was associated with increased risk of heart disease. And given the distribution of erythritol in the American diet, the only way someone could take in that much erythritol is to consume large amounts of erythritol-sweetened highly processed foods.

A brief review of the literature on sweeteners reveals that this is a common pattern for every natural sweetener tested. Low to moderate intake of these sweeteners has no adverse health effects. However, high intake of every sweetener tested in the context of a highly processed food diet is associated with an increased risk of obesity, diabetes, heart disease, and premature death.

That raises the question, “Is it the sweetener, or is it the food?”

Clearly, it doesn’t matter what sweetener we are talking about. Large intake of any natural sweetener in the context of a diet rich in highly processed foods is likely to have an adverse effect on our health. And we don’t know whether these adverse health effects are caused by the sweetener or some other component of a highly processed food diet.

If you want to improve your health, the best solution is to decrease your intake of highly processed foods. That will automatically reduce your intake of sweeteners and other unhealthy components of highly processed foods and increase your intake of healthy components from the whole foods you will be eating instead.

For more details on the study and information about which foods are likely to contain erythritol and the population groups who should be most concerned about erythritol consumption, read the article above.

These statements have not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This information is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure or prevent any disease